Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Darko Zubrinic, Zagreb (1995)

| Since

the whisper of Croatian tongue Can grow Can tie East and West, poem and mind |

Jer hrvatskog jezika sum Moze da goji Moze da spoji Istok i zapad, pjesmu i um |

The

aim of this article is to indicate deep connections between the Croats

and Muslim Bosniaks (= Bosnjaci - Muslimani). In order to avoid

misunderstanding we shall rather use their descriptional name - Muslim

Slavs. The reason is that the Croats in Bosnia are also Bosniaks.

Indeed, many of them bear Bosniak as their second name. The meaning of

Bosniak is simply - a Bosnian.

The

aim of this article is to indicate deep connections between the Croats

and Muslim Bosniaks (= Bosnjaci - Muslimani). In order to avoid

misunderstanding we shall rather use their descriptional name - Muslim

Slavs. The reason is that the Croats in Bosnia are also Bosniaks.

Indeed, many of them bear Bosniak as their second name. The meaning of

Bosniak is simply - a Bosnian.

In the Zagreb telephone book only (1994/95) you can see a long list of as many as 210 surnames of Bosnjak, with only one Muslim forename, and also more than 30 Bošnjakovic's, with only 3 Muslim forenames.

There is village Bosnjaci in Croatia (4,500 inhabitants prior to 1991, near Zupanja). I did not find any village of a similar name on a map of Bosnia. Also in Hrvatsko Zagorje, near Zagreb, there is a

- small village of Bosna, then

- Bosanci near Bosiljevo and Bjelovar,

- Bosnici near Drežnica and Kijevo,

- Bosanka (that is, Bosnian Woman!) near the famous city of Dubrovnik,

- and two small regions of Bosna near Vrbovac and D. Stupnik.

One can find Croatian families bearing the Turkish second name of Ulama even in the NW of Croatia (Hrvatsko Zagorje), as well as Turčić, Turčin, Turčinović, Turčinov, Turk, Poturica, all of them obviously derived from the Turkish name. The town of Tuhelj in Hrvatsko Zagorje was given by those Croats who had to escape from the region of the village of Tuhelj in Bosnia, between Kresevo and Konjic, see [Gizdelin, pp 44, 53]. Near Varazdin Breg there is a village of Turcin (= The Turk). Croatian glagolitic priest fra Matija Bošnjak had to escape from Bosnia in front of the Turks with numerous compatriots. He died in the town of Rab, where on his grave the year of his death, 1525, was chiselled in Croatian Glagolitic characters.

Turčić, Turčin, Turčinović, Turčinov, Turk

Let

us start by describing many traces left

by the Turkish Ottoman Empire. This civilization, that was present on

Croatian soil from the 15th to the 19th century (in eastern parts of

former Yugoslavia until the beginning of the 20th century), left a deep

imprint. Many Croats converted to Islam. The Muslim Slavs are in great

majority of Croatian descent, and constitute now a nation, recognized

according to their own wish in 1968 (Muslimani

has been the

usual name since the beginning of the 20th century). Except in Croatia

they live today mostly in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Sandzak (a province in

the south of Serbia, between Montenegro, Kosovo and Bosnia).

Let

us start by describing many traces left

by the Turkish Ottoman Empire. This civilization, that was present on

Croatian soil from the 15th to the 19th century (in eastern parts of

former Yugoslavia until the beginning of the 20th century), left a deep

imprint. Many Croats converted to Islam. The Muslim Slavs are in great

majority of Croatian descent, and constitute now a nation, recognized

according to their own wish in 1968 (Muslimani

has been the

usual name since the beginning of the 20th century). Except in Croatia

they live today mostly in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Sandzak (a province in

the south of Serbia, between Montenegro, Kosovo and Bosnia).

There

were many

disputes even about the name of "Muslimani", which was defined to have

only the national content (i.e. one could have been Musliman without

being religious at all, as was the case for example with Raif

Dizdarević, former president of former Yugoslavia; of course, his

predecessors were Muslims). On the other hand the term "musliman" (with

small m) had the meaning of Muslim exclusively in the religious sense.

The way out was to choose an old geographical name Bosniak,

which traditionally denoted any citizen of Bosnia - either Croat (as we

said, many of them have Bosniak as a surname), or Muslim, or Serb. It

is strange that this usurpation of the name of Bosniak has been

accepted even in the official Croatia. From this easily follows a

complete usurpation of the Bosnian name (usurpation of Bosnian

literature, language and of the entire history of Bosnia). Of course,

we do not deny the right of Muslim - Bosniaks to call themselves

Bosniaks. We would like to indicate that the name of Bosniaks does not

refer exclusively to Bosnian Muslims, but to Bosnian Croats too.

There

were many

disputes even about the name of "Muslimani", which was defined to have

only the national content (i.e. one could have been Musliman without

being religious at all, as was the case for example with Raif

Dizdarević, former president of former Yugoslavia; of course, his

predecessors were Muslims). On the other hand the term "musliman" (with

small m) had the meaning of Muslim exclusively in the religious sense.

The way out was to choose an old geographical name Bosniak,

which traditionally denoted any citizen of Bosnia - either Croat (as we

said, many of them have Bosniak as a surname), or Muslim, or Serb. It

is strange that this usurpation of the name of Bosniak has been

accepted even in the official Croatia. From this easily follows a

complete usurpation of the Bosnian name (usurpation of Bosnian

literature, language and of the entire history of Bosnia). Of course,

we do not deny the right of Muslim - Bosniaks to call themselves

Bosniaks. We would like to indicate that the name of Bosniaks does not

refer exclusively to Bosnian Muslims, but to Bosnian Croats too.

See also Vladimir

Zerjavic: Muslim-Bosniaks

did not secure the right of autochthony in Croatia.

In Croatian:

"Muslimani-Bossnjaci nisu stekli uvjete authotonosti u Hrvatskoj".

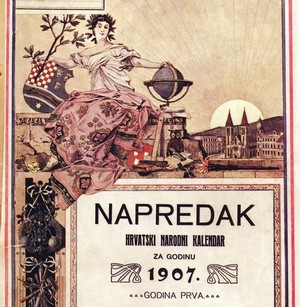

I recommend the interested reader to consult BEHAR, the journal of the Cultural society of Bosniaks (more precisely: Bosniaks - Muslims) in Zagreb called Preporod, for their views on these very sensitive questions, especially an article by Esad Cimic in No22-23, p.12-15, 1996. The society unites outstanding Muslim intellectuals in Croatia. ``Behar'' was founded in 1900 - its first editor in chief had been Safvet-beg Basagic. It was forbidden during the 70 years' ex-Yugoslav period.

Even the historical names of many officials in the Ottoman Empire at Porta reveal their origin (Hirwat = Hrvat or Horvat, which is a Croatian name for Croat):

- Mahmut-pasha Hirwat (= Hrvat)

- Rusten-pasha Hrvat

- Pijali-pasha Hrvat (or Piyale pasha)

- Sijavus-pasha Hrvat, etc.

In the 16th century a

traveler and writer Marco A. Pigaffetta

wrote that almost everybody on the Turkish court in Constantinople

knows the Croatian language, and especially soldiers. Marco Pigafetta

in his "Itinerario'' published in London in 1585 states: "In Istanbul

it is customary to speak Croatian, a language which is understood by

almost all official Turks, especially military men."

More information, with the corresponding documents:

- 7 dokaza da je hrvatski bio službeni jezik u Carigradu na dvoru turskog sultana

This

can also be confirmed by the

1553 visit of Antun

Vrančić, Roman

cardinal, and Franjo Zay, a diplomat, to Istanbul as envoys of the

Croat - Hungarian king to discuss a peace treaty with the Turks. During

the initial ceremonial greetings they had with Rustem - pasha Hrvat (=

Croat) the conversation led in Turkish with an official interpreter was

suddenly interrupted. Rustem - pasha Hrvat asked in Croatian if Zay and

Vrancic spoke Croatian language. The interpreter was then dismissed and

they proceeded in the Croatian language during the entire process of

negotiations.

This

can also be confirmed by the

1553 visit of Antun

Vrančić, Roman

cardinal, and Franjo Zay, a diplomat, to Istanbul as envoys of the

Croat - Hungarian king to discuss a peace treaty with the Turks. During

the initial ceremonial greetings they had with Rustem - pasha Hrvat (=

Croat) the conversation led in Turkish with an official interpreter was

suddenly interrupted. Rustem - pasha Hrvat asked in Croatian if Zay and

Vrancic spoke Croatian language. The interpreter was then dismissed and

they proceeded in the Croatian language during the entire process of

negotiations.

Igitur

quum inter loquendum Verancius loqueretur

ad interpretem, quod passae responderi debebat, conversus passa ad Zay:

Tu, inquit, scisne Croatice? Scieo, respondit. Eti is collega tuus?

Respondit: Ipse quoque... Sed et Verancius itidem, quum eum Croatice ob

quaedam severius dicta lenire vellet, dixit.. (Verancius, 66-67). See [Eterovich],

p. 18. Hrvat Rustem pasha

originates from the region of Makarska, and his original Croatian

second name was Opukovic.

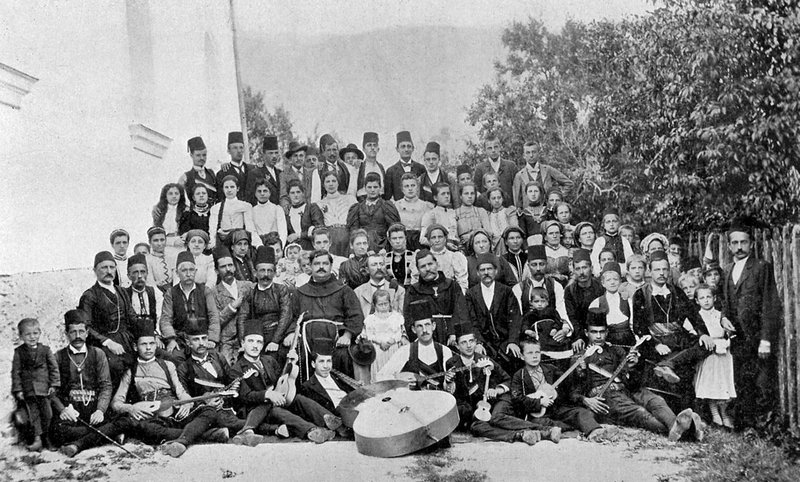

The above two photos are from [Martić].

Piyale Pasha (c. 1515-1578), was a Croatian Ottoman admiral and an Ottoman Vizier. He was also known as Piale Pasha in the West or Pialí Bajá in Spain; Turkish: Piyale Pasa.

One

of the oldest texts written in Arabica

(i.e. Arabitza script, which is in fact Arabic script for the Croatian

language) is a love

song called "Chirvat-türkisi"

(= Croatian song) from 1588,

written by a certain Mehmed

in Bosnia. This manuscript is held

in the National Library in Vienna. Except for literature Arabica was

also used in religious schools and administration. Of course, it was in

much lesser use than other scripts. The last book in Arabica scriopt

was

printed in 1941.

One

of the oldest texts written in Arabica

(i.e. Arabitza script, which is in fact Arabic script for the Croatian

language) is a love

song called "Chirvat-türkisi"

(= Croatian song) from 1588,

written by a certain Mehmed

in Bosnia. This manuscript is held

in the National Library in Vienna. Except for literature Arabica was

also used in religious schools and administration. Of course, it was in

much lesser use than other scripts. The last book in Arabica scriopt

was

printed in 1941.

Some additional names of Muslim Croats who wrote verses using

Arabica script can be found in the chapter "Doprinos muslimana

zajedničkoj i jedinstvenoj hrvatskoj kulturi" (Contributions of Muslims

to the common and unique Croatian culture), on pp. 75-81 of the book [Bakšić]:

- Hadži Jusuf Livnjak (17th ct.)

- Mehmed Hevaji Uskufi (lexicographer, creator of Hrvatsko-turskog rječnika u stihu, i.e., Croatian-Turkish Dictionary in Verses, written 1631)

- Hasan Kaimija Zrinović, derviš, poznat po po jednoj pjesmi u kojoj govori o Hrvatima pod mletačkom vlašću kao dijelu vlstitog naroda

- Hasan Kafi Prušćak (16. st.), Prusac = pogranična tvrđava "Akhisar - Biograd"

- Seid Vehab Ilhamija (16. st.)

- Umihana Čuvidina, prove poznata pjesnikinja muslimanka, jedna od prvih pjesnikinja na hrvatskom jeziku (19. st., rođena oko 1795. u Sarajevu)

- Mula Mustafa Bušaski (ili Ševki - Svjeteli), 18. st.

- Mustafa Firaki (1775.-1809.), sin predhodnog, rođen i umro u Sarajevu

- Hasan Travničan, Jusuf-beg Čengić, Abdulkerim Tefterdarija,

- Omer Humo pisao o aljamiado književnosti

Many of the Muslim Slavs in Bosnia-Herzegovina had a strong awareness of their Croatian descent, and even called themselves Muslim Croats, to distinguish from the Catholic Croats. Some of the most outstanding Croatian writers and intellectuals of the Muslim faith in Bosnia and Herzegovina are:

Edhem

Mulabdić

(1862-1954),

Edhem

Mulabdić

(1862-1954), - Adenaga Mešić (1868-1945),

- Ivan Aziz Miličević (1868-1950),

- Safvet-beg Bašagić (1870-1934), PhD, was a member of JAZU (Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts, in Zagreb) since 1939. In 1945, his membership was revoked by the advent of the new communist Yugoslav rule. The NGO "Dr. Safvet-beg Bašagić" was founded in 2004 in Zagreb, with Mirsad Bakšić as its president. See [Bakšić].

- Osman Nuri Hadžić (1869-1937),

- Hasan Fehim Nametak (1871-1953),

- Fehim Spaho (1877-1942),

- Musa Čazim Čatić (1878-1915),

- Džafer-beg Kulenović (1891-1956),

- Ahmed Muradbegović (1898-1972),

- Hasan Kikić (1905-1942),

- Hamdija Kreševljaković (1898-1959)

- Alija

Nametak (1906-1987), distinguished Muslim-Croatian writer, was

imprisoned by by ex-communist Yugoslav police in the period of

1945-1955. He was a member of Croatian Writers' Association since 1955.

See [Bakšić].

- Nahir Kulenovicć(1929-1969), another Muslim Croat, was assassinated by the ex Yugoslav communist agents in Germany. See [Bakšić].

- Enver Čolaković (1913-1976),

- Mehmedalija Mak Dizdar (1917-1971)

- Muhamed Hadžijahić (1918-1978)

- Ferid Karihman (1930)

- Asaf Durakovic (1940-2020)

- Ekrem Spahić (1945)

etc. Anybody wishing to

study the history of Islamic culture

in Bosnia-Herzegovina seriously should consult numerous works of Hamdija

Kreševljaković (1888-1959), an

outstanding Muslim Croat, member of

the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Zagreb, author of an

important monograph

about history of Croatian

literature in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Biographies of important Muslim

Croats can be found in his Kratak

pregled hrvatske knjige u Herceg -

Bosni (A short survey of Croatian literature in Herzeg - Bosnia)

printed in Sarajevo in 1912. For more information see [Karihman].

We also mention Safvet beg Bašagić (Mirza Safvet), who wrote the monograph, Znameniti Hrvati Bošnjaci i Hercegovci u Turskoj Carevini (Distinguished Croatian Bosniaks and Herzegovinians in the Turkish Empire), published by Matica hrvatska, (Matrix croatica) in Zagreb in 1931.

It should be noted that the literary and scientific activity of such intellectuals has been severely suppressed during the 70 years' ex-Yugoslav period, resulting that today a very small percentage of the entire Muslim Slav population in BiH and Croatia has the awareness of its Croatian roots.

Croatian Muslim centers existed in Munich (Germany), Chicago (USA), Toronto (Canada), Melbourne (Australia). Mirsad Bakšić especially pointed out Croatian Muslim Center in Melbourne, which now gathers numerous Croats of Muslim faith.Distinguished Croatian-American scientist (international expert in radiology) and Croatian-Muslim poet Asaf Durakovic (1940-2020) wrote several booklets dealing with his origins:

- Asaf Duraković: Od Bleiburga do muslimanske nacije, Vedrina, Toronto 1971.

- Asaf Duraković: Mjesto muslimana u hrvatskoj narodnoj zajednici, Vedrina, Toronto 1974.

- Asaf Duraković: Zapisi o zemlji Hrvatskoj.

According to [Bakšić], about 30,000 Muslim Croats participated in the Homeland War 1990-1995. A distinguished figure is Croatian general Nijaz Baflak, better known under the pseudonim Mate Šarlija - Daidža (who was the first brigadier of Croatian Army).

Additional information:

- Ferid Karihman: Los escritores croatas de religión musulmana

- Mato Marčinko: Hrvati islamske vjere

- [Mirsad Bakšić]

We

can document the

equivalence of the name of Bosniak and Hrvat during many centuries,

until the Yugoslav period (see below). It seems that the final and

almost complete national individualization of Muslim Slavs took place

only during the tragedy they experienced during the Serbian large-scale

aggression on Bosnia and Herzegovina in the period of 1992-95 (the

aggression against BiH started already in October 1991 by the slaughter

of the Croats in the Herzegovinian village of Ravno).

This aggression found Muslim

officials totally unprepared. Moreover, when Vukovar and the whole of

Croatia were bleeding, being systematically destroyed in the second

half of 1991, president Izetbegovic declared "This is not our war'',

believing naively that the Yugoslav Army and armed extremists would not

dare to do the same in Bosnia - Hercegovina. Of course, the national

individualization was strengthened also during the tragic conflict with

the Croats in 1993, which was one of the well prepared results of the

Serbian aggression.

We

can document the

equivalence of the name of Bosniak and Hrvat during many centuries,

until the Yugoslav period (see below). It seems that the final and

almost complete national individualization of Muslim Slavs took place

only during the tragedy they experienced during the Serbian large-scale

aggression on Bosnia and Herzegovina in the period of 1992-95 (the

aggression against BiH started already in October 1991 by the slaughter

of the Croats in the Herzegovinian village of Ravno).

This aggression found Muslim

officials totally unprepared. Moreover, when Vukovar and the whole of

Croatia were bleeding, being systematically destroyed in the second

half of 1991, president Izetbegovic declared "This is not our war'',

believing naively that the Yugoslav Army and armed extremists would not

dare to do the same in Bosnia - Hercegovina. Of course, the national

individualization was strengthened also during the tragic conflict with

the Croats in 1993, which was one of the well prepared results of the

Serbian aggression.

The equivalence of the name of Bosniak and Croat in the early period of the Ottoman occupation of Bosnia is documented by the famous Turkish historian Aali (1542-1599) in his work Knhulahbar, also known as Tarihi Aali. He gave the following description of the properties of Croatian tribe (as he calls it) in Bosnia:

As regards the tribe of the Croats, which is assigned to the river Bosna, their character is reflected in their cheerful mood; throughout Bosnia they are also known according to that river... [i.e. Croats = Bosniaks i.e. Bosnians].

Then follows an

interesting passage describing virtues of the

Croats in Bosnia.

Let us cite it in Croatian, in Basagic's translation (the original text

in the Arabic script and its translation can be seen in [Karihman],

p. 78, with the Croatin translation

being taken from Safvet-beg Basagic: Bošnjaci

i Hercegovci u

Islamskoj knjizzevnosti):

Što se tiče plemena Hrvata, koje se pripisuje rijeci Bosni, njihov se značaj odrazuje u veseloj naravi; oni su po Bosni poznati i po tekućoj rijeci prozvati [dakle Bošnjaci]. Duša im je čista, a lice svijetlo; većinom su stasiti i prostodušni - njihovi likovi kao značajevi naginju pravednosti. Golobradi mladići i lijepi momci poznati su (na daleko) po pokrajinama radi naočitosti i ponositosti, a daroviti spisatelji kao umni i misaoni ljudi. Uzrok je ovo, što je Bog - koji se uzvisuje i uzdiže - u osmanlijskoj državi podigao vrijednost tome hvaljenom narodu dostojanstvom i čast njegove sreće uzvisio kao visoki uzrast i poletnu dušu, jer se meddu njima nasilnika malo nalazi. Većina onih, koji su dossli do visokih položaja (u Turskoj državi) odlikuju se veledušjem to jest: čašću i ponosom; malo ih je koji su tjeskogrudni, zavidni i pohlepni. Neustrašivi su u boju i na mejdanu, a u društvu, gdje se uživa i pije, prostodušni. Obično su prijazni, dobroćudni i ljubazni. Osobito se odlikuje ovo pleme vanrednom ljepotom i iznimnim uzrastom... Bez sumnje Bošnjaci, koji se pribrajaju hrvatskom narodu, odlikuju se kao prosti vojnici dobrotom i pobožnosti, kao age i zapovjednici obrazovanošću i vrlinom; ako dođu do časti velikih vezira, u upravi su dobroćudni, ponosni i pravedni, da ih velikaši hvale i odlični umnici slave.''

According

the documents from the

15th and 16th centuries, Bosnian Muslims in central Bosnia and in

Herzegovina called their language Croatian language and called

themselves the Croats. Even today there are Bosnian Muslims with the

second name Hrvat

(= Croat). Islam left valuable written and

architectural monuments, like in Spain for instance. Let us mention

that Croatia's capital Zagreb has one of the biggest and most beautiful

newly built mosques in Europe, although in Turkish time it had none

(Zagreb was never occupied by the Turks). For instance in Belgrade, the

capital of Serbia, there had been several hundred mosques from the

Turkish time, out of which only one survived.

According

the documents from the

15th and 16th centuries, Bosnian Muslims in central Bosnia and in

Herzegovina called their language Croatian language and called

themselves the Croats. Even today there are Bosnian Muslims with the

second name Hrvat

(= Croat). Islam left valuable written and

architectural monuments, like in Spain for instance. Let us mention

that Croatia's capital Zagreb has one of the biggest and most beautiful

newly built mosques in Europe, although in Turkish time it had none

(Zagreb was never occupied by the Turks). For instance in Belgrade, the

capital of Serbia, there had been several hundred mosques from the

Turkish time, out of which only one survived.

Probably the most interesting writings about the life in Ottoman Empire in the 16th century are numerous works published by Bartol Gyurgieuvits (1506-1566), who spent there 13 years as a slave.

In

the province of Molise

in central

Italy there is a small Croatian enclave (about 4,500 people), living

today in several villages, inhabited in 15 villages in the 16th century

by the Croats fleeing before the Turks. They preserved their ethnic

identity and language even today.

In

the province of Molise

in central

Italy there is a small Croatian enclave (about 4,500 people), living

today in several villages, inhabited in 15 villages in the 16th century

by the Croats fleeing before the Turks. They preserved their ethnic

identity and language even today.

Since the 16th century a similar enclave has existed near Bratislava in Slovakia. The largest Croatian community of exiles dating from that period is in the area of Gradisce (Burgenland) in Austria and Hungary. One of the results of this forced migrations is that the most widespread surname in today's Hungary is Horvath, whose meaning is simply Croat. Also the family name Horvat is one of the most widespread in today's Slovenia. The surname Charvat (= Croat) in the present-day Czechia is a remaining of the presence of White Croats on this area since the Early Middle Ages. The family name Horwath and its variations is also very common in Austria (see the telephone book in Vienna). The most famous descendant of Gradisce Croats is without any doubt Joseph Haydn. It is interesting that King Ferdinand I (1515-1564) granted the Burgenland Croats in Austria the right to use Glagolitic Mass, see here.

In Slovenian part of Istria, near Italian border east of Trieste, there is the village of Hrvatini (literally - Croats). Also in Croatian part of Istria, north-east of Zminj, there is the village of Hrvatin. Several Istrian villages have names that are obviously related to those Croats who had to escape before the Turks from the region Lika and Krbava.

Additional information about centuries old Croatian emigration in Czechia and Slovakia can be obtained here:

Today there are several tens of thousands of Croats living in about fifty settlements in the region of Gradisce, i.e. Eisenstadt (about two thirds) and in Vienna (one third). There are 14 Croatian settlements left in Hungary and only four in Slovakia, among them Hrvatski Grob (Croatian Grave) near Bratislava. Specialists estimate that the overall number of Croatian settlements in these regions in the 16th century was as many as 200 to 300! In the 16th century in the area around Bratislava in Slovakia there were about sixty Croatian settlements. See Sanja Vulic, Bernardina Petrovic: Govor Hrvatskoga Groba u Slovackoj, Sekcija DHK i Hrvatkog PEN-a za proucavanje knjizevnosti u hrvatskom iseljenistvu, Zagreb 1999.

In 1722 the Croats in the Hungarian city of Pecuh exiled from Bosnia made 47% of population, in suburbs of Budim (a part of today's Budapest) 80%, and in Siget (Szeged) 53%.

Among descendants of the Croats in Italy we should mention Pope Sixto V (he was the Pope from 1585 to 1590), who spoke Croatian at home.

It is estimated that until the 18th century there were about two million Croats who had been either exiled or taken as slaves to Turkey. Among the Bosnian Catholics there was a large number of Cryptocatholics, i.e. those who were secretly Catholics at home, and ``Muslims'' out of it. Children were circumcised, but secretly baptized as well.

Bosnia and Herzegovina is full of very interesting, mysterious tombstone monuments called stechak (the older names are bilig = sign, mramor = marble, priklopnik or priklopnica = folding). The most famous collection is in Radimlja in Herzegovina:

Here are a few stechak monuments in the vicinity of Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia:

In the middle stechak one can see a lily, which is a very old symbol of Bosnia. In Croatia there are also numerous stechak monuments. Some of them are even near the towns of Knin, Karlovac (Generalski stol), and in Slavonia, near the towns of Pozega and Pakrac.

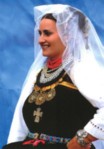

Even

today Croatian women in some parts of

Bosnia tattoo their hands with Christian symbols and stechak

(stećak) ornaments. This very old custom,

used exclusively among Catholic Christians, had a special meaning in

the period of the Ottoman occupation. In this way, by wearing indelible

signs of their Christian religion, the forced conversion to Islam has

been prevented. However, the custom itself is much older. For example,

a Greek historian Strabo (1st century BC) mentions tattooing among

inhabitants of this area. For more information see an article by Ćiro Truhelka: Die Tätowirung

bei den

Katholiken Bosniens und der Hercegovina

(published in Wissenschaftliche

Mittheilungen Aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina,

herausgegeben vom

Bosnisch-Hercegovinischen Landesmuseum in Sarajevo, redigiert von Dr.

Moriz Hoernes, Vierter Band, Wien 1896).

Even

today Croatian women in some parts of

Bosnia tattoo their hands with Christian symbols and stechak

(stećak) ornaments. This very old custom,

used exclusively among Catholic Christians, had a special meaning in

the period of the Ottoman occupation. In this way, by wearing indelible

signs of their Christian religion, the forced conversion to Islam has

been prevented. However, the custom itself is much older. For example,

a Greek historian Strabo (1st century BC) mentions tattooing among

inhabitants of this area. For more information see an article by Ćiro Truhelka: Die Tätowirung

bei den

Katholiken Bosniens und der Hercegovina

(published in Wissenschaftliche

Mittheilungen Aus Bosnien und der Hercegovina,

herausgegeben vom

Bosnisch-Hercegovinischen Landesmuseum in Sarajevo, redigiert von Dr.

Moriz Hoernes, Vierter Band, Wien 1896).

Bosnian Catholic Croats tattoo their hands and other visible parts of body with Christian symbols (usually with a small cross), like brow, cheeks, wrist, or below neck. This can be seen even today, not only in middle Bosnia, but also among exiled Bosnian women living in Zagreb. For more information, see the mnograph [Haluga].

Katarina Vukčić-Kosača

(1424-1478),

the last Queen of Bosnia, ardent Catholic, wife of the Bosnian King Stjepan

Tomasevic (1461-1463), is still

one of the most beloved

personalities among the Croats living in Bosnia. When Bosnia fell under

the Ottoman rule in 1463, her two children (a boy and a girl) had been

taken to slavery and educated in the spirit of Islam, her husband

decapitated. She managed to escape to Dubrovnik,

and then to Rome, where she had been deeply involved in the

humanitarian activity of the Franciscan community (Aracoeli) becoming

Franciscan Tertiary herself, to help Bosnian Croats under the Turkish

rule.

Katarina Vukčić-Kosača

(1424-1478),

the last Queen of Bosnia, ardent Catholic, wife of the Bosnian King Stjepan

Tomasevic (1461-1463), is still

one of the most beloved

personalities among the Croats living in Bosnia. When Bosnia fell under

the Ottoman rule in 1463, her two children (a boy and a girl) had been

taken to slavery and educated in the spirit of Islam, her husband

decapitated. She managed to escape to Dubrovnik,

and then to Rome, where she had been deeply involved in the

humanitarian activity of the Franciscan community (Aracoeli) becoming

Franciscan Tertiary herself, to help Bosnian Croats under the Turkish

rule.

The above portrait of Katarina Kosaca, Bosnian Queen, was made by Giovanni Bellini, held in the Capitol Gallery of paintings in Rome.

She

built a church of St. Katarina in a picturesque Bosnian city of Jajce

(totally destroyed by the Serbs in 1993). Despite her very difficult

position, she had always been treated as a Queen of Bosnia in official

circles. Tormented by the tragedy of her homeland, lawful

Queen

Katarina bequested her Bosnian Kingdom to pope Sixto IV and Holly See

in 1478 ("...in

case that my islamised children are not freed

and returned to Catholic faith").

Her grave in the Aracoeli church

in Rome had a Croatian

Cyrillic inscription

until 1590 (with the coat of arms of the old Bosnian Kingdom and of the

Kosaca family), when it had been replaced by translation into Latin.

Even today, after more than five centuries, Croatian women wear black

costumes in some parts of Bosnia in remembrance to her tragic life and

kindness towards poor people. Beatified.

She

built a church of St. Katarina in a picturesque Bosnian city of Jajce

(totally destroyed by the Serbs in 1993). Despite her very difficult

position, she had always been treated as a Queen of Bosnia in official

circles. Tormented by the tragedy of her homeland, lawful

Queen

Katarina bequested her Bosnian Kingdom to pope Sixto IV and Holly See

in 1478 ("...in

case that my islamised children are not freed

and returned to Catholic faith").

Her grave in the Aracoeli church

in Rome had a Croatian

Cyrillic inscription

until 1590 (with the coat of arms of the old Bosnian Kingdom and of the

Kosaca family), when it had been replaced by translation into Latin.

Even today, after more than five centuries, Croatian women wear black

costumes in some parts of Bosnia in remembrance to her tragic life and

kindness towards poor people. Beatified.

The

seat of Bosnian kings in 14th and

15th centuries was Bobovac,

about 50 km north of Sarajevo. Its

walls were about 1100 meters long. Many documents are preserved

mentioning Bobovac. It fell under the Turks in 1463, which meant the

fall of mediaeval Bosnian state.

The

seat of Bosnian kings in 14th and

15th centuries was Bobovac,

about 50 km north of Sarajevo. Its

walls were about 1100 meters long. Many documents are preserved

mentioning Bobovac. It fell under the Turks in 1463, which meant the

fall of mediaeval Bosnian state.

After the catastrophic defeat of the Serbs in the Kosovo field in 1389, on whose side both Croatian forces from Bosnia and Albanian troops had also participated, Serbia became a vassal state to the Turkish Ottoman Empire.

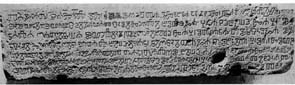

Among

the most tragic events in

the history of the Croats were the Turkish occupation of Bosnia in

1463, and the catastrophic defeat of Croatian defenders in the battle

with the Turks on the Krbavsko

polje (Krbava field in today's Lika)

in 1493. The slaughter of the Croatian

nobility greatly reduced the economic power of the Croatian lands for

the centuries to come. It was described in the "Second Novi Glagolitic

breviary" by rev.

Martinac in 1494 (see a column

from this breviary on the photo). Marko Marulic

wrote his famous Prayer

against the Turks. An extensive

collection of dozens of speeches

"against the Turks" (Orationes contra Turcas) from the middle of the

15th century to the end of the 16th century can be seen in [Gligo],

on 650 pp. Several of these speeches have

been delivered by Croatian noblemen, writers and clergy in front of

Popes, as well as in front of high dignitaries of various European

states.

Among

the most tragic events in

the history of the Croats were the Turkish occupation of Bosnia in

1463, and the catastrophic defeat of Croatian defenders in the battle

with the Turks on the Krbavsko

polje (Krbava field in today's Lika)

in 1493. The slaughter of the Croatian

nobility greatly reduced the economic power of the Croatian lands for

the centuries to come. It was described in the "Second Novi Glagolitic

breviary" by rev.

Martinac in 1494 (see a column

from this breviary on the photo). Marko Marulic

wrote his famous Prayer

against the Turks. An extensive

collection of dozens of speeches

"against the Turks" (Orationes contra Turcas) from the middle of the

15th century to the end of the 16th century can be seen in [Gligo],

on 650 pp. Several of these speeches have

been delivered by Croatian noblemen, writers and clergy in front of

Popes, as well as in front of high dignitaries of various European

states.

These

speeches are important and indelible historical

fact. They do

not have to have any influence on good contemporary relations between

Croatian and Turkey. D.Ž.

In the 16th century the Turks started settling down Serbian population in the emptied regions previously inhabited by the Croatian Catholics. The representatives of the Serbian Orthodox Church had the privilege to collect taxes from the Croatian Catholics. In this way the Serbs wanted to include the Catholics into the Orthodox Church, which was under the control of the Turks (the residence of the Serbian Patriarch was in Constantinople in present-day Turkey).

Let us mention by the way that the animosity of the Orthodox Christians against Catholics was strengthened first in Greece and then in Serbia after the Crusaders had occupied Constantinople and formed the Latin Empire (1204-1261).

Before

the Turkish penetration in the 15th century there were 151 Catholic

churches in Bosnia, about 20 Catholic monasteries, and not a single

Serbian Orthodox church. Several Catholic orders were present in

Bosnia: Benedictines, Paulines, and above all Franciscans. Immediately

after the arrival of the Turks a large number of Serbian Orthodox

churches was built up, many of them on the ruins of Catholic churches.

Under the pressure of the Serbian Clergy many Croatian Catholics had to

convert to the Serbian Orthodox Christian faith. And the religion was

one of the decisive factors in the national affiliation of the people

in Bosnia.

Before

the Turkish penetration in the 15th century there were 151 Catholic

churches in Bosnia, about 20 Catholic monasteries, and not a single

Serbian Orthodox church. Several Catholic orders were present in

Bosnia: Benedictines, Paulines, and above all Franciscans. Immediately

after the arrival of the Turks a large number of Serbian Orthodox

churches was built up, many of them on the ruins of Catholic churches.

Under the pressure of the Serbian Clergy many Croatian Catholics had to

convert to the Serbian Orthodox Christian faith. And the religion was

one of the decisive factors in the national affiliation of the people

in Bosnia.

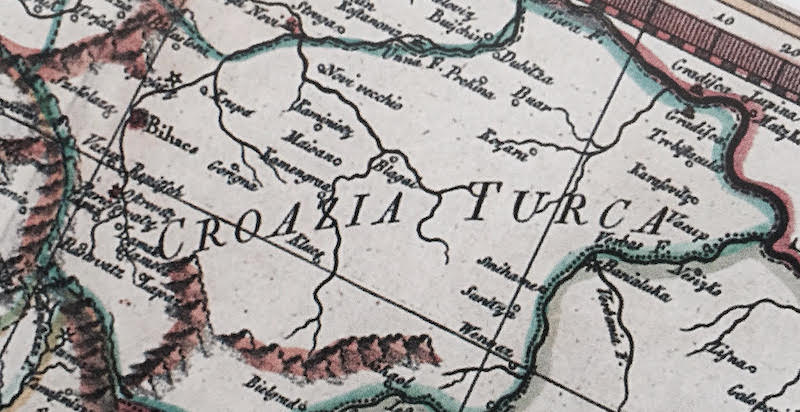

The

border between Middle Age Bosnia and Croatia was on the river Vrbas,

not on Una. The lovely town of Jajce (on river Vrbas) was in Croatia,

as well the town of Bihac. The territories enclosed by three rivers -

Sava, Una and Vrbas - bore the name of the Turkish

Croatia in

the European literature of 18th and 19th century. The name was given by

the Turks, and it was accepted by Austrian, Italian, German and Dutch

cartographers. It was only in 1860 that upon insistance of the Valachian

part of the population the name of Turkish Croatia was abolished in

favor of the new name - Bosanska

Krajina

(Bosnian Frontier). This name appears on maps for the first time in

1869.

The

border between Middle Age Bosnia and Croatia was on the river Vrbas,

not on Una. The lovely town of Jajce (on river Vrbas) was in Croatia,

as well the town of Bihac. The territories enclosed by three rivers -

Sava, Una and Vrbas - bore the name of the Turkish

Croatia in

the European literature of 18th and 19th century. The name was given by

the Turks, and it was accepted by Austrian, Italian, German and Dutch

cartographers. It was only in 1860 that upon insistance of the Valachian

part of the population the name of Turkish Croatia was abolished in

favor of the new name - Bosanska

Krajina

(Bosnian Frontier). This name appears on maps for the first time in

1869.

TURKSICH

KROATIEN, depicted with light

green border in the middle of the

map

from 1799.

TURKSICH

KROATIEN, depicted with light

green border in the middle of the

map

from 1799.

Source of the map Turska

Hrvatska.

CROAZIA TURCA,

depicted on a map published in Rome in 1790.

Below is the same map with more details, slightly rotated

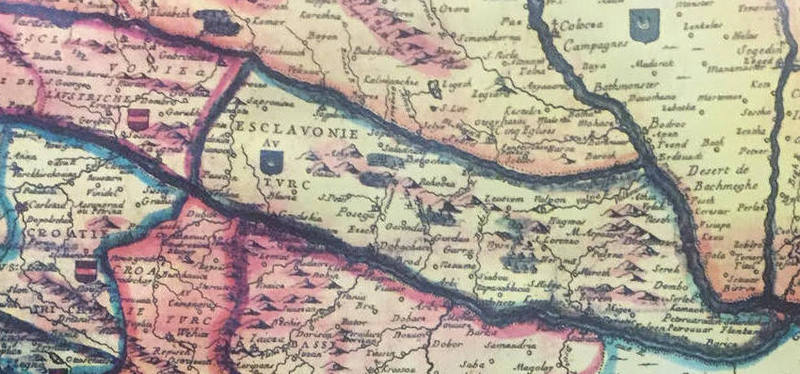

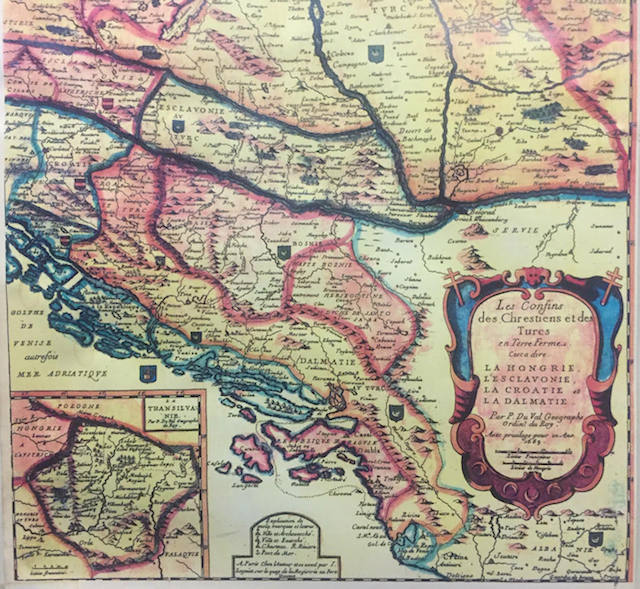

Croatie Turc (in French), part of a map by P. Du Val from 1663:

Les confins des Chrestiens et des Trucs en Terre Ferme, C'est a dire

LA HONGRIE, L'ESCLAVONIE, LA CROATIE et LA DALMATIE.

The whole map also shows Slavonie Turc and Dalmatie Turc, occupied by

the Turks.

CROATIE TURC

ESCLAVONIE TURC

DALMATIE TURC

Franjo Glavinić (1585 - 1652), Croatian Franciscan born in Istria, whose parents were noblemen exiled from Bosnian Kingdom (Glamoc), wrote several important books, among which we cite

- L'origine della Provincia di Bosna Croatia (The Origine of the Province of Bosnia Croatia), two editions, Udine 1648 and 1691; the Province of Bosnian Croatia has been separated from the Province of Bosnia Argentum in 1514 by a decision which took place in the convent of Cetin in Upper Croatia;

- Historia Tersattana, Udine 1648 (History of Trsat, reprinted in 1989),

- Szvitlost duse verne (Light of Faithful Soul; in Croatian, first edition printed in Venice, second in Padova, and third again in Venice), in which he speaks about the human need for virtues here... and to please brothers and faithful, in particular the Croatian people (ugoditi... navlastito Hervackomu jeziku) and my Istrians...

- Czvit szvetih (The Flower of the Sacred People; three editions in Venice), and Chetiri poszlidnya chlovika (The Last Four Men; Venice), both written in Croatian in the monastery of Sv. Leonard near Okic in the vicinity of Samobor.

He has discovered very old and important muniment from 1288 which mentions Stipan from old Dubrovnik, Bishop of Modrus, written in the Glagolitic Script. Here Old Dubrovnik is a town which existed in Middle Bosnia, north of Sarajevo, founded by merchants from the famous Dubrovnik. Old (Stari ) Dubrovnik had existed also after the fall of Bosnia under the Turks in 1463 (nahija Stari Dubrovnik).

See also Pavao Andjelic: Stara bosanska zupa Vidogosca ili Vogosca [PDF], Glasnik Zemaljskog muzeja BiH u Sarajevu, Arheologija, XXVI, 337-346.

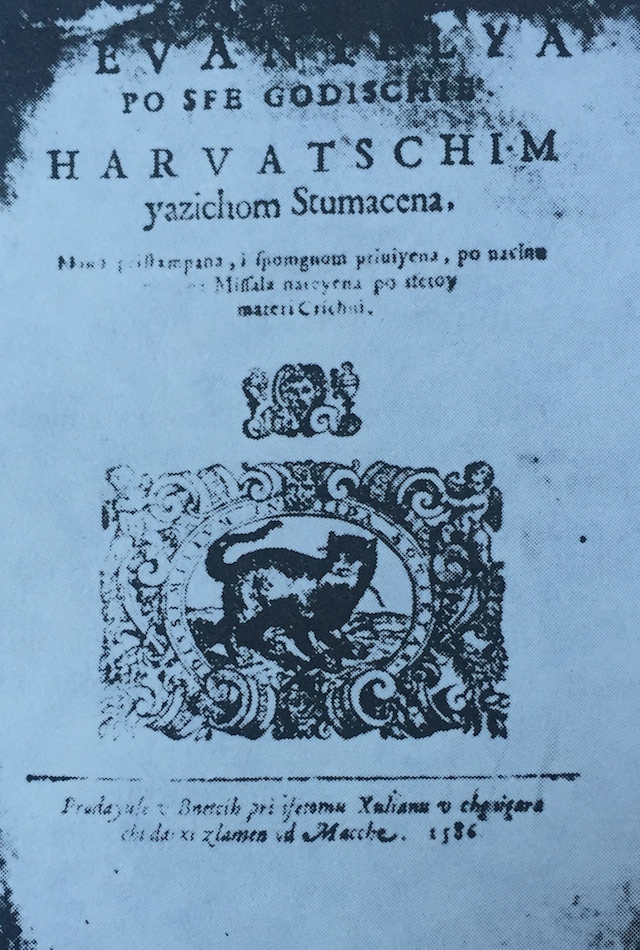

The Evangel from the Franciscan Monastary from Olovo, published in

Venice in 1586,

written in Croatian (HARVATSCHIM yazichom Stumachena = in Croatian

language described).

Photo from Bernardin Matić: Gospa Olovska, drugo preuređeno

izdanje, Svjetlo riječi, Sarajevo 1991.

The territory between Una and Vrbas (former Turkish Croatia) has been ceded to the Serbian entity by the Dayton agreement in 1995. Truly a great success of Milosevic and his apprentices Karadzich and Mladich. The area itself, as well as the fertile region of Bosanska Posavina along the right bank of the Sava river (now also within the Serbian entity), had a large Muslim and Croatian majority in 1991. The region has been almost completely cleansed from the Croats and Muslims that lived there for centuries. A part of cleansing was the so-called "humanitarian exchange of population'' under the auspices of the international community that was not willing to put pressure on Karadzic and Mladic. The European officials describe this as a "compensation'' for the disappearance of the Serbian para-state in Croatia during the Flash and Storm operations.

The Serbs living in Bosnia came with the Turks mostly as assisting Turkish troops. It should be emphasized that these Bosnian Serbs were originally Valachies (Vlachs) from Montenegro and northern Albania. In fact they were non-slavic nomads - Protoromans and romanized Balkan Celts and Illyrians, who accepted the Serbian Orthodox faith (there were also Catholic Valachies in Croatia, croatized after 16th century). Later, under the influence of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Bosnia, they became Serbs. They had been fighting on the Turkish side until the decline of the Turkish Empire started. Their enclaves in present day Croatia follow roughly the border of the Turkish Empire in the medieval Croatia.

Completely destroyed sanctuary of Podmilacje (on the left) and a damaged church near Jajce, after Greater Serbian aggression on BiH (photos by [Čakić-Did])

These migrations led to further complications. Counting on these Serbian settlers as a military aid, the Austrian kings supplied them with privileges. This meant that parts of the Croatian territory were not completely under the Croatian jurisdiction and the Croats felt them as intruders within their state. This was the beginning of the so-called Krajina (`Military Frontier'; "Bosnian Krajina" appeared much later), whose complete and systematic ethnical cleansing from Croats and from everything reminding on their existence was finished during the Serbian aggression 1991-1995. Here we see the beginning of the drama in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Krajina region in Croatia has been liberated during the Flash and Storm operations in the summer 1995.

Let

us continue our story on the history of medieval Bosnia. The tax

in

blood (devshirma) was the most

tragic for Bosnian Catholics. It

meant that every three or four years 300 to 1000 healthy boys and young

men had to be taken by force to Turkey, converted to Islam and educated

for military profession or religious disciplines. Some desperate

mothers even mutilated their children trying to save them.

Let

us continue our story on the history of medieval Bosnia. The tax

in

blood (devshirma) was the most

tragic for Bosnian Catholics. It

meant that every three or four years 300 to 1000 healthy boys and young

men had to be taken by force to Turkey, converted to Islam and educated

for military profession or religious disciplines. Some desperate

mothers even mutilated their children trying to save them.

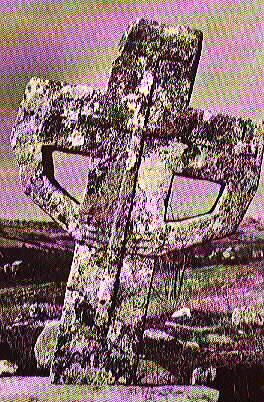

On

the above photo you can see an interesting

cross from the region of Duvno in Herzegovina (about 2 meters high).

According to the legend, it represents a mother whose child was killed

by the Turks. Here is another cross in front of the Fojnica franciscan

monastery (the other side of the cross is ornamented):

After the arrival of the Turks the states of Bosnia and Albania, which had been previously Catholic, became more and more islamized. Moreover, in the same time in Bosnia the Serbian Orthodoxy, supported by the Turks, was spreading. The Jews exiled from Spain (Sefards), who arrived to Bosnia in 1492, were accepted by the Turkish state and exempt from the tax in blood, but not from paying taxes to the Serbian Church.

It is also interesting to note that the language which the Turkish court in Constantinople officially used to communicate with the Balkan Slavs was Croatian. Many islamized Croats were present at the Turkish court as writers, officers, even grand viziers.

The

name of BALKAN = BAL + KAN, consists of two words, the

meaning of which in the Turkish language is BAL - honey, KAN - blood

(which You can easily check using Google Translate; many thanks to Dr.

Emina Kurtagić, Zagreb, for this information). I prefer to avoid

this name.

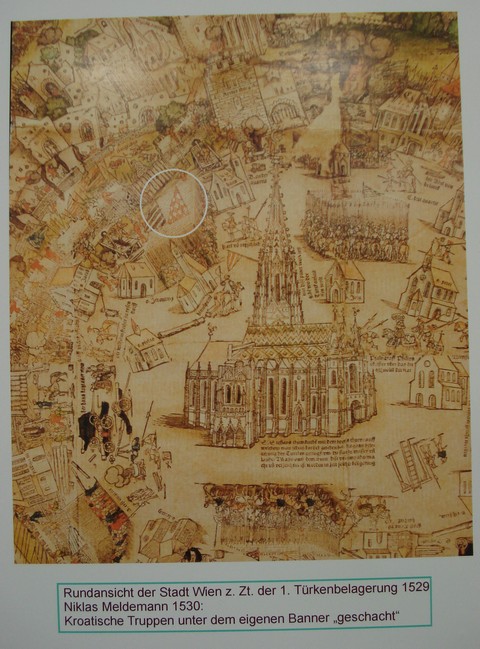

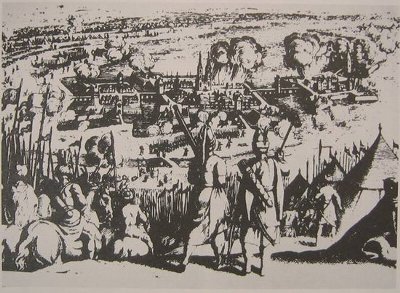

Two clearly visible Croatian Coats of Arms of Croatian troups at the 1526 battle at the Mohac field (Hungary) against the Turks. By the courtesy of Josip Sersic and Mijo Juric, Vienna, 2009. The photo below is a detail, to see larger drawing, click on it.

The city of Vienna, capital of Austria, has been attacked by the Turks already in 1529. Among defensive forces Croatian troups participated under their flag. See encircled below, left of the Stephanusdome, the famous Vienna Cathedral.

For more details see Croatian Coat of Arms.

During the second Turkish siege of Vienna in 1683, a Croatian village called Krowotendörfel, placed immediately near the city walls, has been destroyed, and since then it does not exist any more. The meaning of its name is precisely Croatian Village! Its position corresponded to contemporary Spittelberg near the Hofburg palace. For more details see [400 Jahre Kroaten in Wien]. Other names of Krowotendörfel can also be encountered in the literature:

- Crabathen Derffel

- Crabatendörfel

- Croathndörfel

- Krowotendörfel

- Crabatendoerfel

- Krawattendörfel

- Croatendörfel

- Kroatendörfel ...

Among defenders of Vienna in 1683 was a renowned Croatian theologist and ecumenist panslavist Juraj Krizanic, who was assasinated during the Turkish seige.

In

1526 the disastrous defeat of

Hungarian and Croatian army took place in the Mohač

field in

southern Hungary. Let us mention by the way that since 1991 this area

has offered refuge to 45,000 exiles, mostly Croats from Serbia and

occupied parts of Croatia.

The

territory of western Bosnia, that was

occupied by the Turks only after the battle on the Mohac field, was

called Croatian Bosnia

or Turkish

Croatia

(Bosna hrvatska or Turska Hrvatska) until the Berlin Congress in 1878.

Here is a document depicting cut off heads of Croats killed after the battle at Petrinja near Zagreb in 1592:

The 1592 defeat of Croatian-Habsburg army near Brest was celebrated in Constantinople by showing 29 charriots with 172 captured dignitaries, 600 cut off heads, and 23 captured flags.

A legendary Croatian military commander Nikola Jurišić (born in the town of Senj, 1490-~1545) managed to stop sultan Sulejman the Magnificent (or Great) in 1532 near the town of Köszeg (Güns) at Austrian and Hungarian border. Nikola Jurisic had about 700 Croatian soldiers, the Turks about 32,000 people. The Turkish onsloughts lasted for three weeks. The aim of sultan Sulejman was to occupy Vienna. It is interesting that two years earlier Nikola Jurisic visited sultan Sulejman in Constantinople as a deputy of King Ferdinand.

Marko Stančić Horvat,

Croatian military commander (Gradec, circa 1520 – Siget, 1561),

successfully defended Sziget in 1556 with his infantry consisting of

1000 men, against the attacs of Ali-pasha. The Turcs had about 10,000

victims. Marko Stancic Horvat wrote the book Historia obsidionis et oppugnationis arcis

Zigeth in Ungaria, published in 1557.

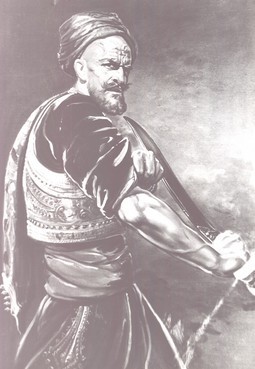

Nikola Zrinski Junior (1620-1664), a Croatian statesman and writer, described in his epic ``The siege of Siget'' the heroic death of his grandfather Nikola Šubić Zrinski in 1566, which entered all the historical annals of the 16th century. With his 2500 brave soldiers, mostly Croats, Nikola Šubić Zrinski was defending the fortress of Sziget in southern Hungary against 90,000 Turks.

The Turkish troops were under the sultan Suleyman the Great and supplied by 300 cannons. It took them a month to defeat the Croatian soldiers, who all died a terrible death in the final battle. Despite his promise, the King Maximillian Habsburg did not help Nikola Šubic Zrinski. Historians say that the Turks had almost 30,000 dead.

Cardinal Richelieu, the famous French minister at the court of King Lui XIII, wrote the following: A miracle was necessary for the Habsburg Empire to survive. And the miracle happened in Sziget. The above mentioned epic was written in the Hungarian language. Though written by the Croat, it is regarded to be one of the greatest achievements of the early Hungarian literature. See also here (in Croatian).

Nikola Šubić Zrinski, his oath taken in Siget in 1566., and his original signature in the Glagolitic script.

Ivan Zajc

has composed the opera

Nikola Subic Zrinski, which is very popular in Japan, especially its

tune "U

boj, u boj!" (on this web page

you can

listen to a Japanese choir singing this song in Croatian!).

See also the monograph published in London in 1664:

- The Conduct and Character of Count Nicholas Serini, London 1664

dealing with Croatian ban

(governer ) and poet Nikola Zrinski Jr. At its very beginning, we can

read the following dedication:

To

All the Admirers of Count Nicholas Serini, The Great Champion of

Christendom.

Among innumerably many Croatian captives in Turkish slavery, there were at least two that deserve special attention:

- Bartol Gyurieuvits (Bartol Jurjevic, Gjurgjevic), 16th century, who left us extremely interesting testimonies about the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire, that can be found in various libraries of almost all larger European cities;

- Juraj Hus (Husti), 16th century, who became Turkish military trumpeter.

It

is not widely known that in the 16th

century the town of Bihac

was Croatian capital. Hasan-pasa

Predojevic, an islamized Croat,

occupied Bihac in 1592. About 2000

people were killed and 800 Croatian children taken to slavery and

educated in the spirit of Islam.

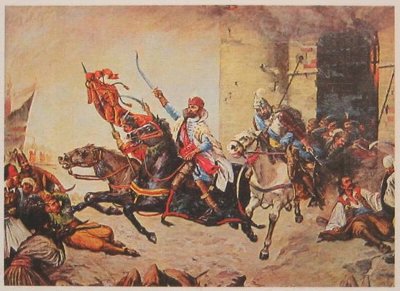

Illustration of the victory of the

Christian army in Croatia (Crabaten) over the Turks in the town Sisak

(Syseck) in 1593 (from Oertler's

Chronology, 1602). Source of the photo [Marković].

A real turning point which meant the beginning of the fall of the Ottoman expansion to Croatian historical lands (and to Europe) was a defeat of Hasan-pasa Predojevic in a battle at Sisak near Zagreb in 1593, which echoed in the whole of Europe.

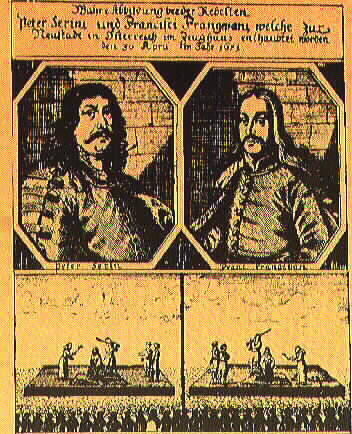

Ban

(Viceroy) Petar Zrinski

(1621-1671) and Fran Krsto

Frankapan

(1643-1671), both outstanding as statesmen and writers, are among the

most beloved figures in the history of Croatia. They had a great

successes in liberating the areas occupied by the Turks. However, the

Viennese Military council, instead of supporting them to free the rest

of the Hungarian and Croatian lands, signed a shameful peace treaty

with Turkey, by which the liberated territories had to be handed back

to the Turks. The result of the rebellion against Vienna was a cruel

public decapitation of Zrinski and Frankapan in Wiener Neustadt near

Vienna in 1671. The remains of these two Croatian martyrs were buried

in the Cathedral of Zagreb in 1919.

Ban

(Viceroy) Petar Zrinski

(1621-1671) and Fran Krsto

Frankapan

(1643-1671), both outstanding as statesmen and writers, are among the

most beloved figures in the history of Croatia. They had a great

successes in liberating the areas occupied by the Turks. However, the

Viennese Military council, instead of supporting them to free the rest

of the Hungarian and Croatian lands, signed a shameful peace treaty

with Turkey, by which the liberated territories had to be handed back

to the Turks. The result of the rebellion against Vienna was a cruel

public decapitation of Zrinski and Frankapan in Wiener Neustadt near

Vienna in 1671. The remains of these two Croatian martyrs were buried

in the Cathedral of Zagreb in 1919.

It is interesting that, while in prison from 18th April 1670 to 30th April 1671, Fran Krsto Frankapan translated Molier's "George Dandin" into Croatian, written in Paris in 1669, ie. only two years earlier. This was was its first European translation. Frankopan is the author of very famous Croatian verses Navik on zivi ki zgine posteno (Forever he lives who dies honorably).

Petar Zrinski was also very educated, being a statesman, poet, composer, polyglot. He presented his legendary sword to the town of Perast in Boka kotorska during his sojourn there in 1654.

The letter sent by Petar Zrinski to his wife Katarina (in Croatian) just a day before his death is one of the most deeply moving texts ever written in the Croatian language. It was very soon translated and published in

- Croatian (Moje drago serce), Vienna, 1671,

- English (My dear soul), London, 1672,

- German (Mein liebes Herz), Vienna, 1671,

- French (Ma chere Femme), Paris, 1691,

- Italian:

- Mio Cuore, Vienna, 1671,

- Carisima Consorte, Dresden, 1672,

- Latin (Delicium meum), Vienna, 1671,

- Spanish (Querida Esposa mia), Madrid, 1687,

- Dutch (Myn Liefste Hert), Amsterdam, 1671,

- Hungarian (Anna Catharina), Budapest, 1671.

His wife Katarina, also an outstanding poetess, was imprisoned by general Spankau in a monastery in Graz, where she went insane and died in extreme poverty. Even the son of Peter and Katarina - Ivan Antun, the last of the Zrinski's, was imprisoned in Graz, solely because he belonged to this outstanding noble family. He died after 20 years of prison in Schlossberg in Graz out of pneumonia. For more details see [Bartolić].

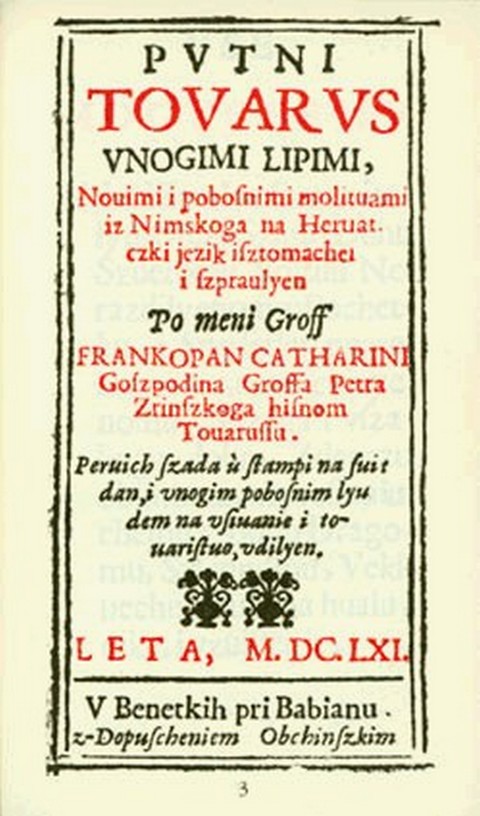

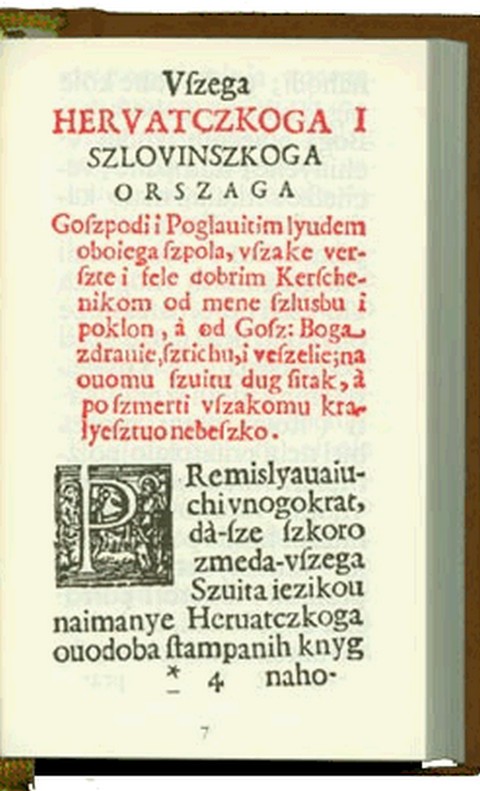

Ana Katarina Frakapan translated a prayer book (Putni tovaruš) from German into Croatian language (Heruatczki jezik) and published in Venice in 1661:

Vsega Hervatczkoga i Szlovinskoga osrzaga... - Of the entire Croatian and Slavonian state...

Velimir Trnski painting the 1671 love story of Petar and Katarina Zrinski

These six centuries old noble Croatian families died out and their property was robbed. It should be stressed that both Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankapan went to Vienna voluntarily, where they have been arrested. During the trial they defended themselves claiming that only Croatian Parliament (Hrvatski Sabor) can try them. In their burgs they had a considerable collection of books and works of art, which after confiscation are held in Austria (many of them in Austrian National Library). A period of the influence of the absolutistic Viennese politics had started.

Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan (1825-1871), by Dr. Vinko Grubišić

- Marc Forstall (Marcus Forestal, +1685), an Irish monk of Augustinian order, was a chancellor of Nikola nad Petar Zrinski. In 1664 he wrote a genealogical treatise about the family of Zrinski, kept in the National and University Library in Zagreb.

- Even today some descendants of the Zrinski family (Sdrin, Sdrinias) live in Greece. See an interesting article by Dionisis pl. Sdrinias (Greece).

photo

from Croatian

Historical Musem

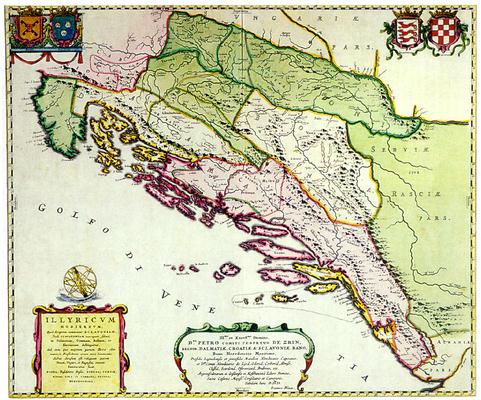

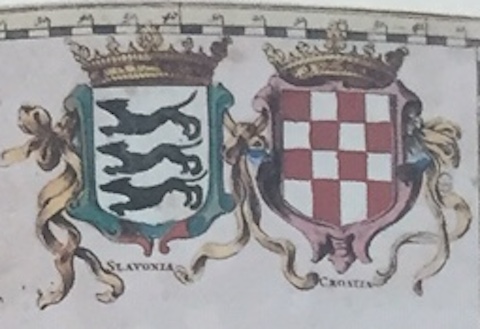

Map dedicated to Petar Zrinski, ban of Croatia. The map was created at the workshop of Joannes Blaeu in Amsterdam as an addition to the work by Ivan Lučić, "De Regno Dalmatiae et Croatiae libri sex", Amsterdam, 1666. Blaeu had inserted the map in Atlas Maior in 1667, and dedicated it to the Croatian ban Petar Zrinski (bottom of the map, in the middle):

To the most illustrious and noble lord, Prince Peter of Zrin, the ban of the Kingdom of Dalmatia, Croatia and Slavonia, hereditary ban of the Littoral, hereditary captain of the Legrad fortress and Medimurje peninsula, master and hereditary prince of Lika, Odorje, Krbava, Omis, Klis, Skradin, Ostrovica, Bribir etc.., Master of Kostajnica and the sliver mine at Gvozdansko, councillor and chamberlain to his anointed imperial majesty, master Ioannes Blaeu dedicates this map.

Text from Croatian Historical Musem. Note Croatian coat of arms on the map.

Ivan Lucic, the first Croatian historiographer: Map of Illyricum (i.e., of Slavonia,

Croatia, Bosnia, Dalmatia),

from the atlas by Dutch cartographer Joan

(or Johannes) Blaeu, 1669. Source of the photo [Markovic].

(Joan Blaeu: A view to Sibenik, during the Turkish occupation in 1645)

This was one of the most dramatic events in the history of this important Croatian city.

Zrin-Frankapan heritage in Croatia: 126 fortresses, castles and bourgs

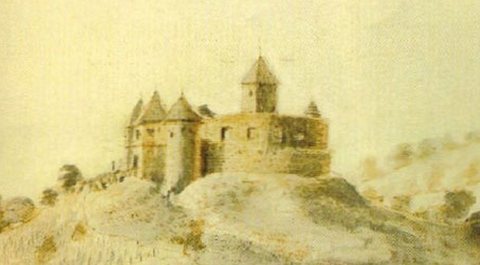

The Gvozdansko fortress in Croatia, between the villages of Dvor (at

that time called Novigrad, on Una river)

and Glina. Drawing from the

17th century.

On Jaunary 13th 1578, after three months of continuous attacks of several thousand soldiers, led by Ferhad pasha, the Turks managed to enter the fortress of Gvozdansko. To their surprise, this time they entered the fortress without any resistence from Croatian side. And upon entering, they saw an amazing scenery: all Croatian defenders (50 soldiers, and 250 peasants and miners with wives and children) were lying dead, frozen in the snow. The soldiers were with arms in their hands. Ferhad pasha was so shocked by what he saw, that he asked a Catholic priest to be found, so that currageous defenders could be burried according to their tradition. The Croatian crew refused several previous Turkish offers to leave the fortess for unoccuopied part of Croatia. They had to struggle not only aginst the Turks, but also against famine and extreme coldness. This is one of the most celebrated events in the military history of Croatia.

We know the names of four captains that led the defense of Gvozdansko:

- Damjan Doktorović

- Juraj Gvozdanović

- Nikola Ožegović

- Andrija Stipšić

- Damir Borovčak: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

- Ugledajmo se u hrabre branitelje gvozdanskog

- Hrvatski vojnik

- Wikipedia

By the 1699 peace treaty in Srijemski Karlovci, the region between the rivers Una and Vrbas was named Turkish Croatia (Turska Hrvatska, Croazia Turca). According to the decisions of the Berlin Congress in 1878 (by which the Habsburg Monarchy obtained a mandate to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina), for the first time was a settlement on the right side of the river Una called Bosnian Dubica (Bosanska Dubica), and the name of Bosnia was extended to the region between the rivers Una and Vrbas.

By

the end of the

17th century some of the occupied parts of Croatia and Hungary were

liberated from the Turks. The Serbs joined Austrian forces (composed

mostly of Croats), hoping to get a full freedom. However, the Austrian

forces were defeated near Skopje in Macedonia. The Turks managed to

regain most of the lost territories, and then a very difficult period

for Serbian people started. Fearing the revenge of the Turks, in 1690

Kosovian Serbs (37,000 families) left for present day Vojvodina, a very

fertile region, the part of which between the rivers Sava and Danube

was a Croatian territory and Hungarian to the north of the Danube.

Actually, the exodus of Serbs included even Budapest. Most of the

Catholic monasteries in Vojvodina became the `property' of the Orthodox

Church, whose aggressiveness made interconfessional relations very

tense. The emptied territories of Kosovo were then populated by the

islamized Albanians. Today the official Serbia quite unjustly claims an

equal right to both Kosovo and Vojvodina.

By

the end of the

17th century some of the occupied parts of Croatia and Hungary were

liberated from the Turks. The Serbs joined Austrian forces (composed

mostly of Croats), hoping to get a full freedom. However, the Austrian

forces were defeated near Skopje in Macedonia. The Turks managed to

regain most of the lost territories, and then a very difficult period

for Serbian people started. Fearing the revenge of the Turks, in 1690

Kosovian Serbs (37,000 families) left for present day Vojvodina, a very

fertile region, the part of which between the rivers Sava and Danube

was a Croatian territory and Hungarian to the north of the Danube.

Actually, the exodus of Serbs included even Budapest. Most of the

Catholic monasteries in Vojvodina became the `property' of the Orthodox

Church, whose aggressiveness made interconfessional relations very

tense. The emptied territories of Kosovo were then populated by the

islamized Albanians. Today the official Serbia quite unjustly claims an

equal right to both Kosovo and Vojvodina.

The

penetration of the Ottoman

Empire to Europe was stopped on Croatian soil, which could be in this

sense regarded as a historical gate of European civilization. Since

1519 Croatia has been known as Antemurale

Christianitatis in

Western Europe. The name was given by Pope Leo X.

The

penetration of the Ottoman

Empire to Europe was stopped on Croatian soil, which could be in this

sense regarded as a historical gate of European civilization. Since

1519 Croatia has been known as Antemurale

Christianitatis in

Western Europe. The name was given by Pope Leo X.

The

Croats endured

the greatest burden of this four century long war against the Turks.

The most tragic fact in this war was that many islamized Croats had to

fight against the Catholic Croats. It is interesting to note that the

city of Zagreb and nearby Sisak despite many attempts were never

occupied by the Turks, though they came as far as Vienna in 1683.

Budapest for instance was in the hands of the Turks for 160 years.

The

Croats endured

the greatest burden of this four century long war against the Turks.

The most tragic fact in this war was that many islamized Croats had to

fight against the Catholic Croats. It is interesting to note that the

city of Zagreb and nearby Sisak despite many attempts were never

occupied by the Turks, though they came as far as Vienna in 1683.

Budapest for instance was in the hands of the Turks for 160 years.

It is in the 17th century that the following very condensed description of the Croatian tragedy was given by Pavao Vitezovic (1652-1713), a writer: ``Reliquiae reliquiarum olim inclyti Regni Croatiae'', i.e. ``Remains of remains of ancient glorious Croatian Kingdom''. Indeed, throughout its long and difficult history its territory has been reduced to the shape of a flying bird.

Present day Croatia is profoundly related to Bosnia-Herzegovina, which is ethnically certainly the most complex state in Europe. It has three major ethnic groups: the Muslims, Serbs and Croats, very intermixed. Let us mention by the way the world-famed Medjugorje, which is in the area inhabited by Croats. During the last ten years it was visited by millions of pilgrims.Bombed by Greater Serbian aggressors in 1992.

The earliest mention of a Catholic diocese in Bosnia dates from 1089 (i.e. from the 11th century). It was called Bosnian Diocese, and its center was in Vrhbosna (today's Sarajevo).

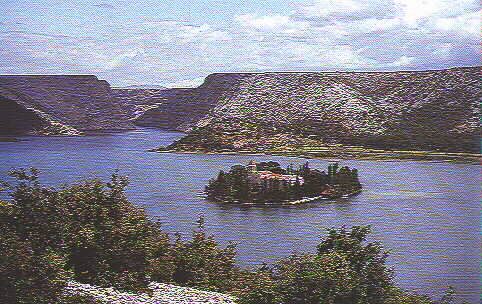

Deep

traces were left by the Bosnian

Franciscans, present on Bosnian

soil since 1291 (only 80 years

after the foundation of the Franciscan order). They were beloved by

people, for being educated and humble, for keeping the national and

religious identity of the Croats. In 1376 they had 35 Catholic

monasteries and about 400 missionaries (the Fojnica

(Hvojnica) monastery is on the

photo on

the left; on the right is the famous Visovac

monastery on the

Krka river, founded in 1445 by Bosnian Franciscans from Kresevo,

middle Bosnia;

shelled by the Serbs in 1991). In Turkish time, by a special Charter (Ahdnama,

1463) from the Sultan, the Bosnian

Franciscans and their Croatian Catholics had a guaranty to live in

peace and freedom in his Empire. However, in reality it was rather

different. Three Franciscan bishops in Bosnia had been killed by the

Turks despite ostensible protection: in 1545, 1564, 1701, not to

mention priests and ordinary people. From 1516 to 1853 a decree was

issued by the Turks that Catholics are not allowed to build new

churches, but only to repair those built before 1463.

Deep

traces were left by the Bosnian

Franciscans, present on Bosnian

soil since 1291 (only 80 years

after the foundation of the Franciscan order). They were beloved by

people, for being educated and humble, for keeping the national and

religious identity of the Croats. In 1376 they had 35 Catholic

monasteries and about 400 missionaries (the Fojnica

(Hvojnica) monastery is on the

photo on

the left; on the right is the famous Visovac

monastery on the

Krka river, founded in 1445 by Bosnian Franciscans from Kresevo,

middle Bosnia;

shelled by the Serbs in 1991). In Turkish time, by a special Charter (Ahdnama,

1463) from the Sultan, the Bosnian

Franciscans and their Croatian Catholics had a guaranty to live in

peace and freedom in his Empire. However, in reality it was rather

different. Three Franciscan bishops in Bosnia had been killed by the

Turks despite ostensible protection: in 1545, 1564, 1701, not to

mention priests and ordinary people. From 1516 to 1853 a decree was

issued by the Turks that Catholics are not allowed to build new

churches, but only to repair those built before 1463.

Kraljeva Sutiska (or Kraljeva Sutjeska = Royal Gorge)

An

old and contemporary inscriptions in Croatian

Cyrillic

in Kraljeva sutiska

(on the left: + V ime Bozje,

se lezi Radovan Pribilović, na svojoj

zemlji plemenitoj, na Ricici; bih s bratom se razmenio, i ubi me Milko

Božinić, sa svojom bratijom; a brata mi isikoše i učinise vrhu mene krv

nezaimitnu vrhu; Nek (zna) tko je moj mili.

Even some of Catholic

churches built before 1463 were

transformed into Muslim mosques (for example in Foca, Bihac, Jajce,

Srebrenica, etc.). So in 18th century only three monastic Catholic

churches were left (in Fojnica, Kraljeva Sutiska and in Kresevo), and

two small churches (in Podmilacje and Vares), see [Gavran,

IV, p. 103.

About

Ahdnama and the question of its

authenticity see two articles by Sasa Sjeverski in Stecak, Sarajevo,

56/1998, pp 28-29, and 57/1998, pp 14-15.

An outstanding European intellectual of his time was Georgius Benignus (Juraj Dragisic, ?1454 - 1520), a Croat born in Bosnia, in the town of Srebrenica.

Today the richest library in Bosnia-Herzegovina is in the Franciscan monastery of Mostar (bombed by the Serbs in 1992). The most famous Croatian Franciscan is St. Nikola Tavelic (born in Sibenik about 1340-1391), a missionary in Bosnia and Yerusalem, a martyr whom Pope Paul VI proclaimed a Saint in 1970. We should also mention another Franciscan-capuchin, St. Leopold Mandic (1866-1942), who was a forerunner of today's Ecumenism.

The Franciscan province in Bosnia was called

Bosna Srebrena (Bosnia Argentum)

i.e.

Silver Bosnia.

Since the 19th century its site is in Sarajevo. This very old name was

derived from the name of the city of SREBRENICA

which in pre

turkish times (before the end of the 15th century) had been known as an

important Catholic center in north-eastern Bosnia (in Croatian srebro =

silver). Due to the existence of the famous Franciscan monastery in

Srebrenica, the whole Franciscan province in Bosnia obtained its name

from it. Srebrenica was also an important mining center, known from the

Roman times. It had been settled also by the Dubrovnik merchants and

Saxonian miners from Germany. Even today there is a small village near

Srebrenica called Sase, whose name has been derived from the name of

Saxons.

i.e.

Silver Bosnia.

Since the 19th century its site is in Sarajevo. This very old name was

derived from the name of the city of SREBRENICA

which in pre

turkish times (before the end of the 15th century) had been known as an

important Catholic center in north-eastern Bosnia (in Croatian srebro =

silver). Due to the existence of the famous Franciscan monastery in

Srebrenica, the whole Franciscan province in Bosnia obtained its name

from it. Srebrenica was also an important mining center, known from the

Roman times. It had been settled also by the Dubrovnik merchants and

Saxonian miners from Germany. Even today there is a small village near

Srebrenica called Sase, whose name has been derived from the name of

Saxons.

We know that in the region of north-eastern Bosnia, to which also the city of Srebrenica belongs, there existed a large number of Catholic churches and six Franciscan monasteries. This witnesses about deeply rooted Catholic tradition in this area before the Turkish occupation in the second half of the 15th century.

The

names of many toponyms in this area,

as well as elsewhere, reveal its Croatian origin:

- HRVATSKE njive (HRVAT = CROAT) on the river Drina near Zvornik,

- the nearby village HRVACICI,

- the village of HRVATI near Tuzla,

- HRVATI near Brcko,

- HRVATSKO brdo near Repnik,

- HRVATOVCI near Gradacac,

- the village BISKUPICI (Biskup = bishop; and not Episkopici'') etc.

Now we would like to provide an impressive list of

i.e. monasteries that we know to have existed before the Turkish occupation of Bosnia in 1463.

|

Central

and western Bosnia:

|

Northern

and north-eastern Bosnia:

Hum (today's Herzegovina):

|

Just for comparison, immediately before the Serbian aggression that started in 1991/92 Bosnian Franciscans had altogether 25 monasteries (three of them outside of Bosnia - Herzegovina: two in Belgrade and one in the Kosovo region).

This list is for sure not complete, but it tells us already enough. It is clear that Catholic churches in Bosnia were much more numerous than Franciscan monasteries. According to the Turkish census of population in Bosnia from 1570 even the city of Foca on the river Drina had Catholic majority at that time. The ethnic and religious picture of Bosnia - Herzegovina has changed especially drastically in the 17th and 18th centuries in favor of Muslims and Orthodox Christians.

In

1658 a Franciscan Ivan

from Foča sent a

request to

the Pope in the Vatican for permission to use Croatian language, "as

was allowed to all priests in the province of Dalmatia" (...come pure

concesta a tuti gli sacerdoti della provincia di Dalmazia), meaning of

course the Croatian

Glagolitic liturgy. See [Strgačić],

p. 388.

Here Foča

is a small town on the north of Bosnia (in

Bosanska Posavina, between the towns of Derventa and Doboj), and

not Foca on the river Drina. Many thanks to Mr. Ilija Ika Ilic for this

information.

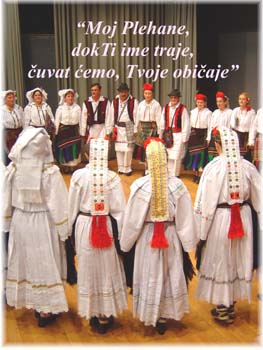

Very

important

franciscan monastery of Plehan

with the accompanying

church have been completely destroyed in 1992., using two tons of

explosive, during Greater Serbian aggression on Bosnia - Herzegovina

(1991-1995), see [

Photo from www.plehan.ch

Very valuable library, museum and historical archives in Plehan have been burnt down. For more information see Project Plehan, Plehan - a Beacon for Croatians in Bosnia, an interview with Fra Mirko Filipovic in Glas Koncila, and Bosna Srebrena.

A well known fact from the history of Bosnia (as well as recent) is that successes in the defense of the Croatian territories from Turkish onslaughts were followed by savage reprisals over the remaining Croatian Catholics in occupied areas (in today's Bosnia - Herzegovina and parts of Croatia). In this way many Catholic churches and monasteries disappeared and large ares in Bosnia had been emptied from the Croats. Especially infamous was gazi Husref - Beg, army leader of sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (16th century).

In this way the emptied areas had been populated by Muslim and Valachian settlers. Catholic churches were transformed into mosques like in Srebrenica, nearby Zvornik on the river of Drina, and in many other places.

An

important and interesting phenomenon

of Bosnian history are Krstyans,

members of the mysterious Bosnian

Church - a Christian religious

sect. Krstyans are also known under

the name of Good Christians (Dobri Krstyani). According to studies of fra Leon Petrovic,

reports of Hungarian clergy to the

Pope in 13th century about the "heresy" of Bosnian Krstyans were

unfounded. The "heresy" of Bosnian Krstyans was invented by church

authorities in Budim in order to subjugate Bosnia to Hungary first in

ecclesiastic, and then in political sense. This policy succeeded to

separate Bosnia from the Dubrovnik

Archdiocese (which was also accused for "heresy"!), and to attach it

to the Hungarian Archdiocese in Kalocsa in 1247. Several crusades

against Bosnian "heretics" had been undertaken in the 13th century.

According to recent investigations, their overall number in the 15th

century was already small compared to the Catholic population in Bosnia

(Turkish sources recorded only 700 Krstyans in 1468/69, see [Gavran,

IV, p. 101). They all disappeared with the

fall of Bosnia under Turks in 1463.

According

to Franjo Sanjek, claims about massive

passage of Bosnian and Herzegovinian Krstyans to Islam are historically

unfounded. See his article "Dobri

Muz'je" Crkve bosanskih i humskih

krstjana in Stecak 58/1998,

Sarajevo. See also [Sanjek].

The history of Krstyans of Bosnian

Church is studied in an illuminating monograph [fra

Leon Petrovic].

It is interesting that they had institutions of their own that they called hizha (house), while the bishop of the Bosnian Church was did (= grandfather), both typically Croatian names, in dialectal use even today. They were never called ``hristjans'' or ``hrischans'', as would be the case if they were of the Serbian provenance. The institution of "did" existed also in old Croatian Kingdom, until its union with Hungary in 1102.

Another important and well documented fact regarding Krstyans in Bosnia is that liturgical books of the Bosnian Church had been transliterated from the Croatian Glagolitic sources into Croatian Cyrillic (Bosancica). Thus Krstyans are very closely related to the Croatian Glagolitic tradition.

Croatian Glagolitic sources related to Bosnia and Herzegovina (see also [Damjanovic, Glagoljica na podrucju danasnje BiH]):

- Kijevci fragment found near Kozara mountain found in NW Bosnia, 11/12th centuries, in its character very close to Glagolitic stone inscriptions in Western Slavonia (12/13th centuries) discovered in 1996,

- the Gršković fragment of Apostle (12th century),

- the Mihanović fragment of Apostle (12th century),

- inscription of prince Miroslav from Omis, 12th century (Croatian Cyrillic and Glagolitic),

- short Glagolitic inscription from Posusje (Grac), containing only two letters (T or V), according to Branko Fucic 12/13th centuries, see [Damjanović, Glagoljica na tlu današnje BiH]

- a leaf of Glagolitic parchment, known as the Split fragment (12/13th centuries), held in the treasury of the Split Cathedral, probably from Bosnia,

- Glagolitic

inscription in Livno, (content:

A SE PI /

SA LU / KA DI / AK / 13 / 6 / 8) 1368, (and three more fragments,

groblje sv. I've)

[1] [2] [3] [4]

Many thanks to dr. fra Bono Vrdoljak, Livno, for this information - Sokolska isprava, Glagolitic quickscript document from 1380, from western Bosnia (at that time part of Croatia, in Turkish time called Turkish Croatia),

- Kolunići inscription, 14/15th centuries, found near Bosanski Petrovac, with OSTOJA inscribed twice (the first one is mirror, in reverse order), see [Fucic]

- Inscription from Dragelja, south of Bosanska Gradiska, lost (there is no photo or drawing)

- Čajniče Evangelistary, 14/15th centuries, contains a part written in the Glagolitic script (St John, 17-20), and a Glagolitic alphabet (incomplete and rather deformed),

- Glagolitic inscription from Bihać (kept in Fojnica), is still studied,

- two glagolitic fragments on parchment from 14th century are today in the Franciscan Monastery Livno (Gorica)

- Glagolitic document from Ostrozac near Bihac in BiH, 1403, vellum with seal on purple silk ribbon, (kept in the archives of prices' of Auersperg in Ljubljana in 1890's, today probably in National Library of Ljubljana, [Lopasic, p. 294]),