A CROATIAN COMPOSER

NOTES TOWARD THE STUDY

OF

JOSEPH HAYDN

First edition in 1897, London,

reprinted in 1972, New York.

Joseph Haydn (1738-1809). Pencil sketch

by George Dance, 1794.

Source of the photo Classical

Music Pages.

[EXAMPLES]

EXCERPTS from the book from p. 40 to p. 65.

p. 40 ...It will be remembered that for thirty years, from 1761 to 1790, he worked as Prince Esterhazy's Kapellmeister in the very centre of the Croatian colony. He must have heard these songs every day, he must have set his life to their lilt and cadence; they were the melodies of his own people, the echoes of his own thought. No one is surprised that Burns should have gathered the Ayrshire peasant songs and transmuted them into gold by the fire of his genius; it is not more wonderful that Haydn should have enriched the treasures of Eisenstadt with metal from his native mines, and as Heine pertinently puts it, the Temple is built by the Architect, not by the stonecutters who supply him with his materials.

Among the numerous illustrations collected by Dr. Kuhac, the following deserve special attention.

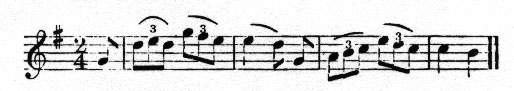

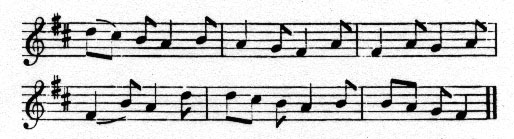

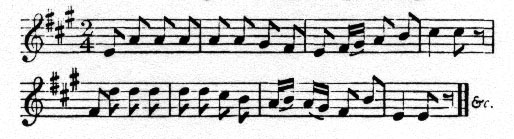

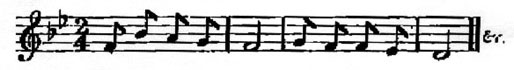

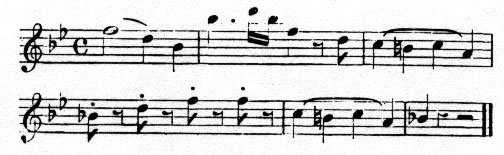

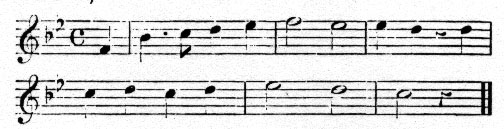

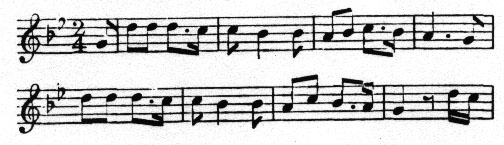

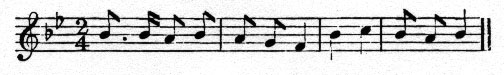

(1) The Cassation in G major (1765) begins as follows:

a melody noticable for the breaking of the four-quaver rhythm by alternate bars of six. It can hardly be doubted that when Hadyn worte this he had in his mind the old Slavonic drinking song, "Nikaj na svetu" -

variants of which may still be heard in Croatian, and in the Carinthian Zillerthal. Similar instances of slight adaptation may be traced from the spring song, "Proljece"-

which appears at the beginning of the D major Quartet (Op. 17, No. 16) as-

and from the dance-song "Hajde malo dere"-

which is thus altered by Haydn-

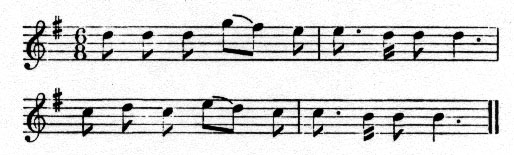

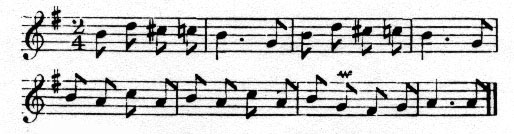

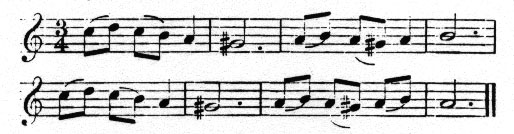

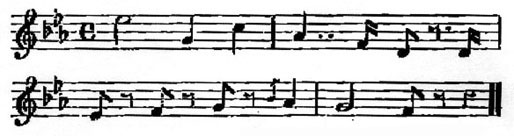

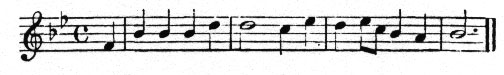

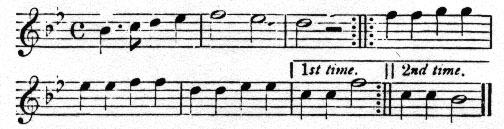

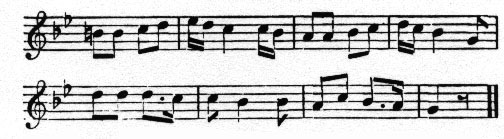

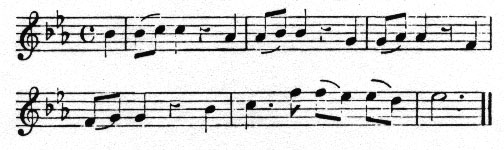

(2) The curious and characteristic finale of the D major Symphony (Salomon, No.7) is founded on the following theme:-

This is simply an amended version of the popular ballad, "Oj Jelena," which belongs to the district of Kolnov, near Oedenburg, and is specially noted by Dr. Kuhac as being commonly sung in Eisenstadt. Its tune, essentially Slavonic in rhythm and cadence, runs thus:-

Variants of this melody are found in Croatia proper, Servia, and Carniola *(See Kuhac, "South Slavonic Popular Songs," vol. iii. pp. 98-100.)

It is probable that the other movements of this symphony are equally influenced by folksongs; in any case, no doubt can exist as to the Symphony in Eb, "Mit dem Paukenwirbel." The opening theme of the Allegro-

is noted by Dr. Kuhac as Croatian. The Andante is founded on two themes, the first minor-

the second major-

both of which are taken, and considerably improved, from two folksongs of the Oedensburg district, (a) "Na Travniku"-

and (b) "Jur Postaje"-

while the principal tune of the Finale-

is that of the song "Divojcica potok gazi"-

which is common among the Croats, especially those of Haydn's district. Again, the Trio of the A major Symphony (No. 11 in Haydn's Catalogue) contains a Slavonic melody-

and the first movement of its successor (D major, No. 12) suggests another-

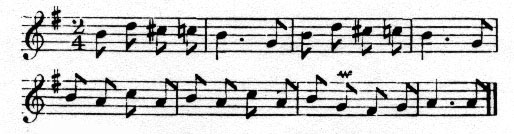

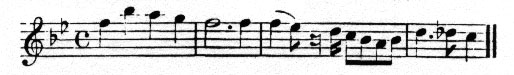

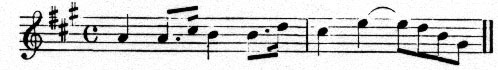

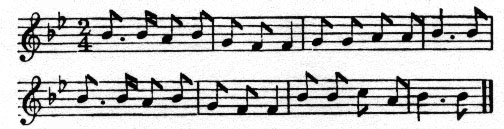

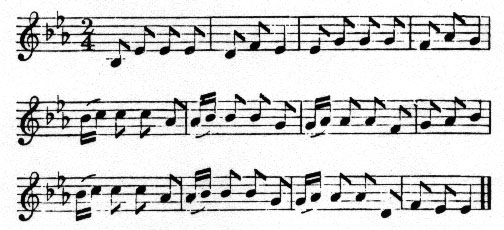

p. 47 (3) There are several cases in which, without direct adaptation, Haydn has shown the same tendency of thought or phrase as the Slavonic folksongs. A favourite "curve" of his may be illustrated by the opening of the Bb Symphony (Salomon, No. 9)-

as well as by the Dalmatian Overture of Franz von Suppé and the tunes (from Zara and Boristov) on which it was founded - e.e, the ballad "Na placi sem stal"

Another, even more beautiful, end the opening strain in the Adagio of the G Major Quartet (Op. 77, No. 1) -

and appears also in the4 Croatian "Cujes doro dobro moje" -

while the use of the unprepared dominant ninth, construcet out of a dominant seventh by shifting the melody a third hither, was not so common in Haydn's day that we can afford to neglect the resemblance of -

quoted by Dr. Kuhac from a Quartet in Bb, to -

from a popular folksong of Carniola.

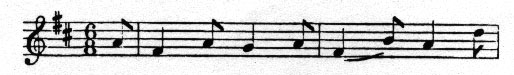

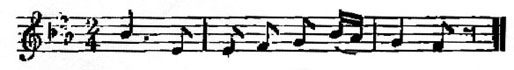

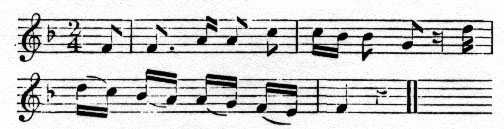

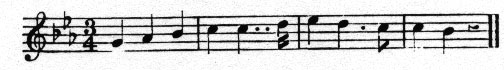

(4) These latter examples do not imply reminiscences, but at most a general sympathy of temper. A good deal more, however, is involved in the treatment of Slavonic dance tunes. It is hardly too much to say that what the Csardas was to Liszt the Kolo was to Haydn; with this difference - that the earlier and greater musician has throughout made a finer use of his materials. The Kolo is a Slavonic measure, which I have seen the children dance at Agram [=Zagreb] and the men at Sarajevo, bright and cheery of movement, its tune in two-four time ingeniously varied by patterns of quaver and semiquaver figures. Here, for instance, is an example well known in Bosnia and Dalmatia:-

and used with an amended cadence in the Finale of the C major Quartet (Op. 33, No. 3):-

p. 53 ...This melody [Finale of the G major Quartet (Op. 77., No. 1)], which contains no Magyar characteristics, either of figure, scale, or stanza, is compressed from that of the Siri Kolo, as commonly danced in Bosnia and Dalmatia. The complete tune runs:-

a typical rustica dance, which in Haydn's hands has gained not only by compression, but by a more artistic accompaniment.

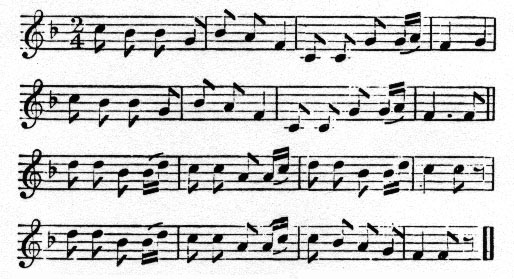

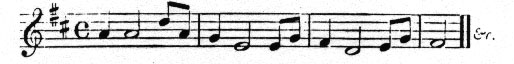

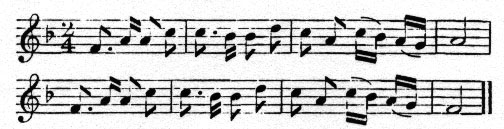

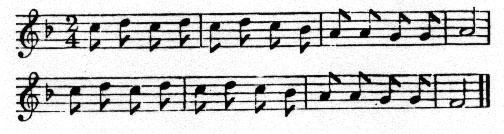

p. 55 (5) In addition to the dance measure, Haydn has adopted other instrumental forms, e.g., marches, bag-pipe melodies, and the like. Here is one, with a strange rhythm, from the Pianoforte Scherzando in F major: -

and here, from the Finale of the Bb Symphony (Salomon, No. 9) is the march which is commonly played in Turopol at rustic weddings:-

Another Croatian march beginning-

has been identified by Dr. Kuhac from an unpublished Symphony in A major; and there is further example from the Allegro of the Bb Quartet (Op. 71, No. 1) -

(6) The two most remarkable instances are yet to come. According to a well-known story, Prince Esterhazy once discussed with his Kapellmeister [Haydn] the question whether Church music could not be made "at the same time religious and popular." It is hard to realise that Haydn's Masses were ever regarded as too severe; in any case, the Prince felt dissatisfied, and wanted a change. He had recently returned from his annual pilgrimage to Maria Zell. He had heard there music which pleased him, and he seems to have suggested that in the Eisenstadt chapel there was too much counterpoint and too little melody. Haydn listened, sent to Maria Zell for information, bided his time, and, when next year the day of the pilgrimage was approaching, wrote a "Mass" or Service to German words, despatched it to the famous church, had it secretly practised and finally found an excuse for slipping off on a holiday. The Prince came back more dissatisfied than ever. "I have heard," he said, "a service of Church music composed and played in a style which you will never equal." "Your Highness," answered Haydn, "the composition was mine, and I was the organist."

From this "Mass," of which at present no other trace seems to be discoverable, Dr. Kuhac quotes seven melodies on the authority of the Dominican Alois Russwurm who was a personal friend of Haydn, and by whom the story was originally recorded.

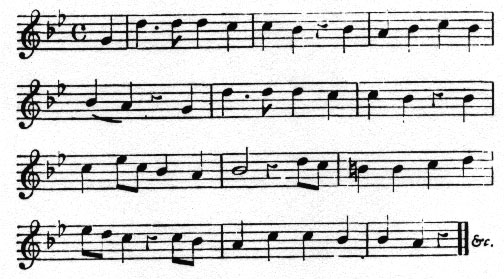

The first, "Hier liegt vor Deiner Majestät," is the opening theme of the first number-

and comes from the Croatian tune-

The second, "Gott soll gepriesen werden"-

is the song "Ti jabuka," as sung in Velik-Boristov-

The third, "Allmäachtiger, vor Dir im Staube,"-

begins remarkably like the Slavonian drinking song, "Draga moja gospodo."

The fourth, " Vater, sieh vor Deinem Throne"-

may fairly be regarded as a variant of the Dalmatian song, "Jedna Ciganka"-

The fifth, "Betrachtet ihn in Schmerzen"-

is almost identical in both parts with the following Croatian melody:-

The sixth- "Nun ist das Lamm geschlachtet"-

is derived partly from two separate strains in the Croatian versions of a convivial chorus- "Vivla compagnija"-

(a)-

(b)-

partly from a Croatian sacred song- "Stani gori gospodar."

The seventh- "Dich wahres Oesterlamm"- which is the concluding phrase of the canticle for the Celebration.-

borrws its exact sequence and its curious halting rhythm from the Croatian "Misi prave svatove"-

Clearly, in Haydn's vocabulary "popular" meant Slavonic.

It may be objected that this example proves nothing. Grant that Haydn was living in a certain district, and that he was asked for once to write in a popular style; what more natural than that he should adapt himself to his surroundings, and use the idioms that he found in common currency?

p. 63 ...(The Croatian melodies) are bright, sensitive, piquant, but seldom rise to any high level of dignity or earnestness. They belong to a temper which is marked rather by felling and imagination than by any sustained bredth of thought, and hence, while they enrich their own field of art with great beauty, there are certain frontiers which they rearly cross, and from which, if once crossed, they soon return.

...In almost all the examples quated above, it is the opening of the tune which Haydn has borrowed; its conclusion he has nearly always improved or re-written. And the reasons that impelled him to this practice may be illustrated by the following variants, in all of which are apparent the same touch of inspiration, and the same weakness of development.

Back to Sir W.H. Hadow: A Croatian Composer; notes towards the study of Joseph Haydn